How ‘productive play’ is helping leaders overcome employee resistance to AI

Key Points

To counter employee fear of AI, some leaders are reframing adoption not as a mandate, but as a low-stakes invitation to “play.”

Jessica DeLorenzo, CHRO at Kimball Electronics, champions this philosophy, arguing that experimentation creates a safe space to fail and learn without pressure.

DeLorenzo introduces a “playground principle,” explaining that clear guardrails are what give employees the freedom to experiment safely and effectively.

She stresses that success depends on leaders modeling curiosity and vulnerability, noting that employees are three times more likely to use AI if they see their manager doing so.

If you're 'playing,' there's not that pressure of getting it right or wrong. It creates a safe space to fail fast. [With AI] you have to experiment, fail, fine-tune, try again, and continue to iterate with it.

Jessica DeLorenzo

Chief Human Resources Officer

Kimball Electronics

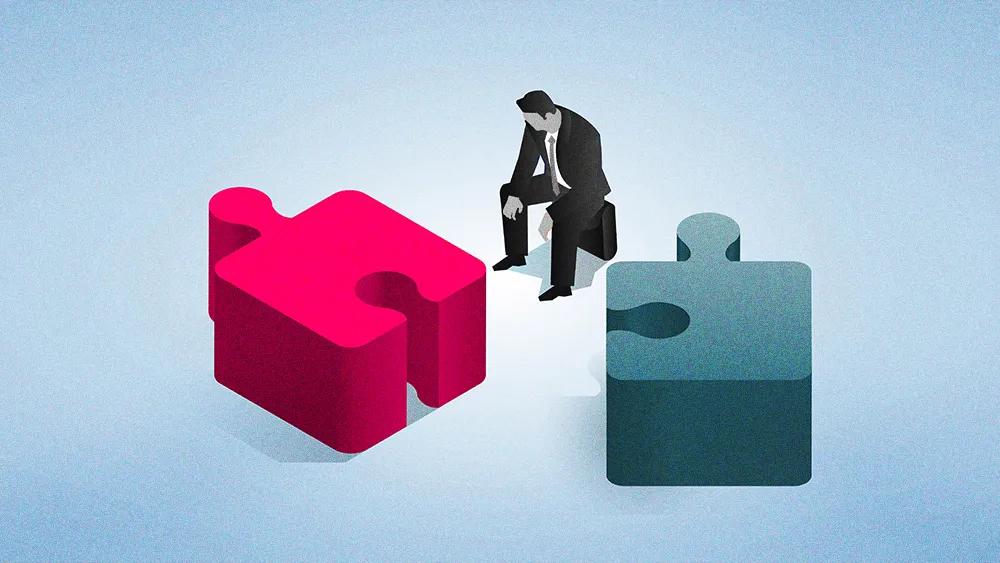

For some employees, the arrival of new AI tools is met with a quiet dread, fearing job irrelevance or being outpaced by algorithms. But what if the most effective antidote to this pervasive anxiety isn’t a top-down mandate or a technical training blitz? What if the secret to AI adoption lies in giving people “permission to play“?

That’s the philosophy championed by Jessica DeLorenzo, the Chief Human Resources Officer at Kimball Electronics, a global $1.3B contract manufacturer with more than 6,500 employees worldwide. As a fundamental behavior change, DeLorenzo argues HR is in a strong position to lead the AI adoption conversation.

Play thing: “If you’re ‘playing,’ there’s not that pressure of getting it right or wrong,” she says. “It creates a safe space to fail fast. You have to experiment, fail, fine-tune, try again, and continue to iterate with it.” To make this concept tangible, DeLorenzo had her team engage in a low-pressure exercise: creating their own AI-generated action figures.

Red flag: The key insight came from what the AI got wrong, driving a discussion around the difference between machine output and human insight. “My team always makes fun of me for wearing red shoes, but the AI-generated figure didn’t have them,” she says. “A human teammate would have known to include the shoes as a part of my persona, but AI didn’t have that nuance. It sparked a conversation about what it got right, what it got wrong, and why.”

To make the play approach work, DeLorenzo says, leaders need to actively model the behavior they want to see. Its success depends heavily on their willingness to demonstrate curiosity and vulnerability, which gives their teams the psychological safety to experiment. “As the leader, I went first, and I think that gave my team permission to play and try it,” she says. “Leading by example is so important for this behavioral change. Research shows that if an employee sees their leader using AI, they are three times more likely to use it themselves.”

Playground principle: Of course, encouraging play in a corporate environment immediately raises questions of risk and security. DeLorenzo’s counterpoint is the “playground principle,” which explains that clear rules are what create the conditions for freedom. “Yes, it’s play, but it’s also important to pause before you jump right in. You need to make sure you’re in the right platform with the right guardrails in place,” she says. “Think of a playground. There might be a fence around it, but within that fence, it’s free rein. As long as that guardrail exists and people are clear what it is, you can get a lot done.”

Her human-centric approach extends to measuring success for AI adoption. For DeLorenzo, understanding people’s emotional response is a key part of refining the adoption strategy. It’s how you uncover the subtle anxieties that pop up even after the initial threat of job loss has passed. One such anxiety is the fear of social judgment. “I’ve seen research that says some people are hesitant to use AI because of the perception their coworkers will have of them, specifically the fear of being seen as lazy.”

To move employees past these hesitations, she explains that the same modeling concept must be scaled down to frontline managers, who need their own hands-on experience with the technology. “It’s about giving managers the scaffolding and toolsets to respond to their people in different ways,” DeLorenzo says. “That starts by encouraging the managers to use it themselves. If they don’t have direct experience with AI, they can’t coach the high adopters or build advocacy in the low adopters.”

There are two potential paths for AI, as DeLorenzo sees it. The first is a future where people become “less diligent,” taking AI output at face value instead of applying their own judgment. The other is the potential to unlock human creativity, using AI as a “thought partner and a coach.” Which path a company follows, she says, is heavily influenced by the culture and mindset its leaders build.

As the leader, I [experimented with AI] first, and I think that gave my team permission to play and try it. Leading by example is so important for this behavioral change. Research shows that if an employee sees their leader using AI, they are three times more likely to use it themselves.

Jessica DeLorenzo

Chief Human Resources Officer

Kimball Electronics

As the leader, I [experimented with AI] first, and I think that gave my team permission to play and try it. Leading by example is so important for this behavioral change. Research shows that if an employee sees their leader using AI, they are three times more likely to use it themselves.

Jessica DeLorenzo

Chief Human Resources Officer

Kimball Electronics

Related articles

TL;DR

To counter employee fear of AI, some leaders are reframing adoption not as a mandate, but as a low-stakes invitation to “play.”

Jessica DeLorenzo, CHRO at Kimball Electronics, champions this philosophy, arguing that experimentation creates a safe space to fail and learn without pressure.

DeLorenzo introduces a “playground principle,” explaining that clear guardrails are what give employees the freedom to experiment safely and effectively.

She stresses that success depends on leaders modeling curiosity and vulnerability, noting that employees are three times more likely to use AI if they see their manager doing so.

Jessica DeLorenzo

Kimball Electronics

Chief Human Resources Officer

Chief Human Resources Officer

For some employees, the arrival of new AI tools is met with a quiet dread, fearing job irrelevance or being outpaced by algorithms. But what if the most effective antidote to this pervasive anxiety isn’t a top-down mandate or a technical training blitz? What if the secret to AI adoption lies in giving people “permission to play“?

That’s the philosophy championed by Jessica DeLorenzo, the Chief Human Resources Officer at Kimball Electronics, a global $1.3B contract manufacturer with more than 6,500 employees worldwide. As a fundamental behavior change, DeLorenzo argues HR is in a strong position to lead the AI adoption conversation.

Play thing: “If you’re ‘playing,’ there’s not that pressure of getting it right or wrong,” she says. “It creates a safe space to fail fast. You have to experiment, fail, fine-tune, try again, and continue to iterate with it.” To make this concept tangible, DeLorenzo had her team engage in a low-pressure exercise: creating their own AI-generated action figures.

Red flag: The key insight came from what the AI got wrong, driving a discussion around the difference between machine output and human insight. “My team always makes fun of me for wearing red shoes, but the AI-generated figure didn’t have them,” she says. “A human teammate would have known to include the shoes as a part of my persona, but AI didn’t have that nuance. It sparked a conversation about what it got right, what it got wrong, and why.”

To make the play approach work, DeLorenzo says, leaders need to actively model the behavior they want to see. Its success depends heavily on their willingness to demonstrate curiosity and vulnerability, which gives their teams the psychological safety to experiment. “As the leader, I went first, and I think that gave my team permission to play and try it,” she says. “Leading by example is so important for this behavioral change. Research shows that if an employee sees their leader using AI, they are three times more likely to use it themselves.”

Jessica DeLorenzo

Kimball Electronics

Chief Human Resources Officer

Chief Human Resources Officer

Playground principle: Of course, encouraging play in a corporate environment immediately raises questions of risk and security. DeLorenzo’s counterpoint is the “playground principle,” which explains that clear rules are what create the conditions for freedom. “Yes, it’s play, but it’s also important to pause before you jump right in. You need to make sure you’re in the right platform with the right guardrails in place,” she says. “Think of a playground. There might be a fence around it, but within that fence, it’s free rein. As long as that guardrail exists and people are clear what it is, you can get a lot done.”

Her human-centric approach extends to measuring success for AI adoption. For DeLorenzo, understanding people’s emotional response is a key part of refining the adoption strategy. It’s how you uncover the subtle anxieties that pop up even after the initial threat of job loss has passed. One such anxiety is the fear of social judgment. “I’ve seen research that says some people are hesitant to use AI because of the perception their coworkers will have of them, specifically the fear of being seen as lazy.”

To move employees past these hesitations, she explains that the same modeling concept must be scaled down to frontline managers, who need their own hands-on experience with the technology. “It’s about giving managers the scaffolding and toolsets to respond to their people in different ways,” DeLorenzo says. “That starts by encouraging the managers to use it themselves. If they don’t have direct experience with AI, they can’t coach the high adopters or build advocacy in the low adopters.”

There are two potential paths for AI, as DeLorenzo sees it. The first is a future where people become “less diligent,” taking AI output at face value instead of applying their own judgment. The other is the potential to unlock human creativity, using AI as a “thought partner and a coach.” Which path a company follows, she says, is heavily influenced by the culture and mindset its leaders build.