Swapping HR for ‘People Ops’ leaves companies at the mercy of untrained managers

Key Points

Bolt’s shift to “People Ops” from HR may cut red tape, but also lead to biased employment decisions and legal risks.

Putting managers in the place of HR creates a dangerous precedent of managers making decisions based on personal feelings without HR oversight.

The lack of HR expertise in compliance could expose companies to costly legal challenges.

Most managers are never formally trained to be managers. We forget that. HR is their sounding board, their source for insight and support. Take that away, and you're not just risking compliance—you're abandoning your managers and their teams.

Jessica Smith

Principal

HRisThriving

When payments company Bolt recently dismantled its HR department in favor of “People Ops,” it was framed as a move to cut red tape and empower managers. But in the rush to eliminate a bureaucratic roadblock, leaders risk creating a much bigger problem: a vacuum of objectivity that exposes the entire organization to the costly whims of human bias.

Jessica Smith is the Principal of HRisThriving and former Human Resources Consulting Director at investment advisory services firm CliftonLarsonAllen (CLA). With decades of experience building and scaling people functions, she explains that without a neutral third party, companies become dangerously vulnerable to the one thing org charts can’t control: feelings.

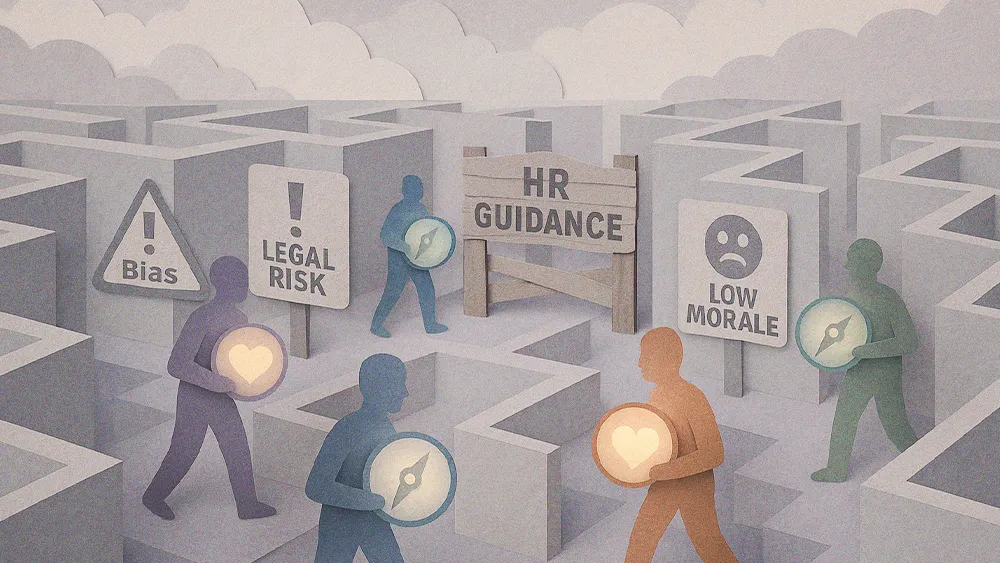

The ‘irk’ factor: The greatest risk in an HR-free business model, Smith warns, isn’t procedural—it’s human. When managers become the sole arbiters of performance and fit, personal feelings inevitably enter the equation, often with subtle but damaging consequences. “People are people. A manager might just be irked by an employee who is not a star performer, but is good enough,” Smith explains. “Without HR, what stops that manager from acting on that feeling?”

This seemingly small friction can easily escalate into inconsistent treatment across teams, creating a culture where employment decisions are driven by personal bias rather than fair process. “Our role,” she adds, “is to ensure one person’s feelings aren’t what drives an employment action.”

An army of untrained leaders: That risk is compounded by an often-overlooked reality: most managers were promoted for their performance, not their people skills. “Most managers are never formally trained to be managers,” Smith notes. “We forget that. HR is their sounding board, their source for insight and support. Take that away, and you’re not just risking compliance—you’re abandoning your managers and their teams.”

A compliance minefield: Perhaps the most tangible danger in stripping away HR is offloading legal compliance onto managers who are, by definition, not experts. A decentralized approach might seem efficient, but it ignores the patchwork nature of US employment law, “In the US, many states have a great deal of variation in their employment laws,” Smith explains. “Some cities and counties have their own variations. Running afoul of those can be potentially very costly in time and money.”

A symptom, not the source: This willingness to expose the company to such risk is often a sign of deeper issues. When leaders see their people function as a problem to be solved, Smith says, they’re often misdiagnosing what is likely a cultural misalignment. “If leaders feel that HR is just ‘gumming up the works,’ it’s not an HR problem,” she says. “It’s a sign of a fundamental misalignment between the function, the leadership, and the company culture.”

The CFO blind spot: The dangerous calculation of treating HR as a discretionary expense often gets made during times of economic instability. Smith says such risky cost cutting would never be applied to other functions. Companies would never dream of skimping on their CFO, she notes, because they understand the non-negotiable value of wise financial guidance.

Right-sized, not one-size-fits-all: The investment in HR teams, Smith adds, can be “right-sized” to an organization’s culture and scale through fractional leadership or consulting, providing seasoned guidance without the full-time overhead. She insists the same standard must apply to the any people-focused function. “The value that HR brings needs to be understood,” Smith says. “It’s worth the investment.”

If leaders feel that HR is just ‘gumming up the works,’ it’s not an HR problem. It’s a sign of a fundamental misalignment between the function, the leadership, and the company culture.

Jessica Smith

Principal

HRisThriving

If leaders feel that HR is just ‘gumming up the works,’ it’s not an HR problem. It’s a sign of a fundamental misalignment between the function, the leadership, and the company culture.

Jessica Smith

Principal

HRisThriving

Related articles

TL;DR

Bolt’s shift to “People Ops” from HR may cut red tape, but also lead to biased employment decisions and legal risks.

Putting managers in the place of HR creates a dangerous precedent of managers making decisions based on personal feelings without HR oversight.

The lack of HR expertise in compliance could expose companies to costly legal challenges.

Jessica Smith

HRisThriving

Principal

Principal

When payments company Bolt recently dismantled its HR department in favor of “People Ops,” it was framed as a move to cut red tape and empower managers. But in the rush to eliminate a bureaucratic roadblock, leaders risk creating a much bigger problem: a vacuum of objectivity that exposes the entire organization to the costly whims of human bias.

Jessica Smith is the Principal of HRisThriving and former Human Resources Consulting Director at investment advisory services firm CliftonLarsonAllen (CLA). With decades of experience building and scaling people functions, she explains that without a neutral third party, companies become dangerously vulnerable to the one thing org charts can’t control: feelings.

The ‘irk’ factor: The greatest risk in an HR-free business model, Smith warns, isn’t procedural—it’s human. When managers become the sole arbiters of performance and fit, personal feelings inevitably enter the equation, often with subtle but damaging consequences. “People are people. A manager might just be irked by an employee who is not a star performer, but is good enough,” Smith explains. “Without HR, what stops that manager from acting on that feeling?”

This seemingly small friction can easily escalate into inconsistent treatment across teams, creating a culture where employment decisions are driven by personal bias rather than fair process. “Our role,” she adds, “is to ensure one person’s feelings aren’t what drives an employment action.”

An army of untrained leaders: That risk is compounded by an often-overlooked reality: most managers were promoted for their performance, not their people skills. “Most managers are never formally trained to be managers,” Smith notes. “We forget that. HR is their sounding board, their source for insight and support. Take that away, and you’re not just risking compliance—you’re abandoning your managers and their teams.”

Jessica Smith

HRisThriving

Principal

Principal

A compliance minefield: Perhaps the most tangible danger in stripping away HR is offloading legal compliance onto managers who are, by definition, not experts. A decentralized approach might seem efficient, but it ignores the patchwork nature of US employment law, “In the US, many states have a great deal of variation in their employment laws,” Smith explains. “Some cities and counties have their own variations. Running afoul of those can be potentially very costly in time and money.”

A symptom, not the source: This willingness to expose the company to such risk is often a sign of deeper issues. When leaders see their people function as a problem to be solved, Smith says, they’re often misdiagnosing what is likely a cultural misalignment. “If leaders feel that HR is just ‘gumming up the works,’ it’s not an HR problem,” she says. “It’s a sign of a fundamental misalignment between the function, the leadership, and the company culture.”

The CFO blind spot: The dangerous calculation of treating HR as a discretionary expense often gets made during times of economic instability. Smith says such risky cost cutting would never be applied to other functions. Companies would never dream of skimping on their CFO, she notes, because they understand the non-negotiable value of wise financial guidance.

Right-sized, not one-size-fits-all: The investment in HR teams, Smith adds, can be “right-sized” to an organization’s culture and scale through fractional leadership or consulting, providing seasoned guidance without the full-time overhead. She insists the same standard must apply to the any people-focused function. “The value that HR brings needs to be understood,” Smith says. “It’s worth the investment.”